The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

| The Wonderful Wizard of Oz | |

|---|---|

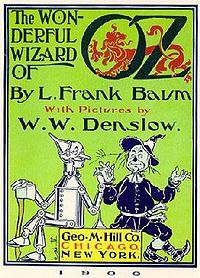

Original title page. |

|

| Author | L. Frank Baum |

| Illustrator | W. W. Denslow |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | The Oz Books |

| Genre(s) | Fantasy Children's novel |

| Publisher | George M. Hill |

| Publication date | 1900 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback), Audiobook |

| Pages | 259 p., 21 leaves of plates (first edition hardcover) |

| ISBN | N/A |

| OCLC Number | 9506808 |

| Followed by | The Marvelous Land of Oz |

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is a children's novel written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by W.W. Denslow. It was originally published by the George M. Hill Company in Chicago on May 17, 1900,[1] and has since been reprinted countless times, most often under the name The Wizard of Oz, which is the name of both the 1902 stage play and the extremely popular, highly acclaimed 1939 film version. The story chronicles the adventures of a girl named Dorothy in the Land of Oz. Thanks in part to the 1939 MGM movie, it is one of the best-known stories in American popular culture and has been widely translated. Its initial success, and the success of the popular 1902 Broadway musical Baum adapted from his story, led to Baum writing thirteen more Oz books.

Baum dedicated the book "to my good friend & comrade, My Wife", Maud Gage Baum. In January 1901, the publisher, the George M. Hill Company, completed printing the first edition, which probably totaled around 35,000 copies. Records indicate that 21,000 copies were sold through 1900.[2]

The original book has been in the public domain in the United States since 1956. Baum's thirteen sequels entered public domain in the United States from 1960 through 1986. The rights to these books were held by the Walt Disney Company, and their impending expiration was a prime motivator for the production of the 1985 film Return to Oz, based on Baum's second and third Oz books.

Historians, economists and literary scholars have examined and developed possible political interpretations of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. However, the majority of the reading public simply takes the story at face value.

Contents |

Plot summary

Dorothy is a girl who lives in a farmhouse in Kansas with her Uncle Henry, Aunt Em, and little dog Toto. One day the farmhouse, with Dorothy and Toto inside, is caught up in a tornado (although it is referred to as a cyclone in the book) and deposited in a field in the Land of the Munchkins in the Land of Oz. The falling house kills the ruler of the Munchkins, the Wicked Witch of the East.

The Good Witch of the North comes with the Munchkins to greet Dorothy and gives Dorothy the Silver Shoes that the Wicked Witch of the East had been wearing when she was killed. In order to return to Kansas, the Good Witch of the North tells Dorothy that she will have to go to the "Emerald City" or "City of Emeralds" and ask the Wizard of Oz to help her.

On her way down the road paved with yellow brick, Dorothy frees the Scarecrow from the pole he is hanging on, restores the movements of the rusted Tin Woodman with an oil can, and encourages them and the Cowardly Lion to journey with her and Toto to the Emerald City. The Scarecrow wants to get a brain, the Tin Woodman a heart, and the Cowardly Lion, courage. All are convinced by Dorothy that the Wizard can help them too. Together, they overcome obstacles on the way including narrow pieces of the yellow brick road, Kalidahs, a river, and the Deadly Poppies.

When the travelers arrive at the Emerald City, they are asked to use green spectacles by the Guardian of the Gates. When each traveler meets with the Wizard, he appears each time as someone or something different. To Dorothy, the Wizard is a giant head; the Scarecrow sees a beautiful woman; the Tin Woodman sees a ravenous beast; the Cowardly Lion sees a ball of fire. The Wizard agrees to help each of them, but one of them must kill the Wicked Witch of the West who rules over the Winkie Country.

As the friends travel across the Winkie Country, the Wicked Witch sends wolves, crows, bees, and then her Winkie soldiers to attack them but they manage to get past them all. Then, using the power of the Golden Cap, the Witch summons the Winged Monkeys to capture all of the travelers.

When the Wicked Witch gains one of Dorothy's silver shoes by trickery, Dorothy in anger grabs a bucket of water and throws it on the Wicked Witch, who begins to melt. The Winkies rejoice at being freed of the witch's tyranny, and they help to reassemble the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman. The Winkies love the Tin Woodman and they ask him to become their ruler, which he agrees to do after helping Dorothy return to Kansas.

Dorothy uses the Golden Cap to summon the Winged Monkeys to carry her and her companions back to the Emerald City, and the King of the Winged Monkeys tells how he and the other monkeys were bound by an enchantment to the cap by Gayelette.

When Dorothy and her friends meet the Wizard of Oz again, he tries to put them off. Toto accidentally tips over a screen in a corner of the throne room, revealing the Wizard to be an old man who had journeyed to Oz from Omaha long ago in a hot air balloon.

The Wizard provides the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion with a head full of bran, pins, and needles ("a lot of bran-new brains"), a silk heart stuffed with sawdust, and a potion of "courage", respectively. Because of their faith in the Wizard's power, these otherwise useless items provide a focus for their desires. In order to help Dorothy and Toto get home, the Wizard realizes that he will have to take them home with him in a new balloon, which he and Dorothy fashion from green silk. Revealing himself to the people of the Emerald City one last time, the Wizard appoints the Scarecrow, by virtue of his brains, to rule in his stead. Dorothy chases Toto after he runs after a kitten in the crowd, and before she can make it back to the balloon, the ropes break, leaving the Wizard to rise and float away alone.

Dorothy turns to the Winged Monkeys to carry her and Toto home, but they cannot cross the desert surrounding Oz. The Soldier with the Green Whiskers advises that Glinda, the Good Witch of the South (changed to the "North" in the 1939 film), may be able to send Dorothy and Toto home. They, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion journey to Glinda's palace in the Quadling Country. Together they escape the Fighting Trees, dodge the Hammer-Heads, and tread carefully through the China Country. The Cowardly Lion kills a giant spider, who is terrorizing the animals in a forest, and he agrees to return there to rule them after Dorothy returns to Kansas—the biggest of the tigers ruling in his stead as before. Dorothy uses her third wish to fly over the Hammer-Heads' mountain, almost losing Toto in the process.

At Glinda's palace, the travelers are greeted warmly, and it is revealed by Glinda that Dorothy had the power to go home all along. The Silver Shoes she wears can take her anywhere she wishes to go. She tearfully embraces her friends, all of whom will be returned, through Glinda's use of the Golden Cap, to their respective sovereignties: the Scarecrow to the Emerald City, the Tin Woodman to the Winkie Country, and the Cowardly Lion to the forest. Then she will give the Cap to the king of the Winged Monkeys, so they will never be under its spell again. Dorothy and Toto return to Kansas and a joyful family reunion. The Silver Shoes are lost during Dorothy's flight and never seen again.

Illustration and design

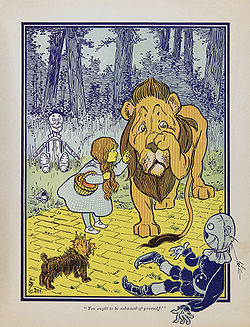

The book was illustrated by Baum's friend and collaborator W.W. Denslow, who also co-held the copyright. The design was lavish for the time, with illustrations on every page, backgrounds in different colors, and several color plate illustrations. The distinctive look led to imitators at the time, most notably Zauberlinda, the Wise Witch. The typeface was the newly designed Monotype Old Style.

Sources of images and ideas

Baum acknowledged the influence of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, which he was deliberately revising in his "American fairy tales" to include the wonder without the horrors.[3]

Local legend has it that Oz, also known as The Emerald City, was inspired by a prominent castle-like building in the community of Castle Park near Holland, Michigan where Baum summered. The yellow brick road was derived from a road at that time paved by yellow bricks. These bricks were found in Peekskill, New York where Baum attended the Peekskill Military Academy. Baum scholars often reference the 1893 Chicago World's Fair (the "White City") as an inspiration for the Emerald City. Other legends allude that the inspiration came from the Hotel Del Coronado near San Diego, California. Baum was a frequent guest at the hotel, and had written several of the Oz books there.[4] Baum said that the name "OZ" came from his file cabinet labeled "O-Z"[5] Another influence lay in the Alice books of Lewis Carroll. Although he found their plots incoherent, Baum identified their source of popularity as Alice herself, a child with whom the child readers could identify; this influenced his choice of a protagonist.[3]

The Gold Standard representation of the story

In 1964, Henry Littlefield claimed that the book contained an allegory of the late 19th-century debate regarding monetary policy[6] According to this view, the "Yellow Brick Road" represents the gold standard, the silver slippers (ruby in the film version) represent the sixteen to one silver ratio (dancing down the road). The thesis achieved some popular interest and elaboration[7] but is not taken seriously by literary historians.[8][9][10]

Cultural impact

The Wizard of Oz has been translated into well over forty different languages, at times being modified in local variations. For instance, in some abridged Indian editions, the Tin Woodman was replaced with a snake.[11]

Russian author Alexander M. Volkov brought his own loose translation of the story to the Soviet Union in 1939[12] (the same year MGM released their film). The Soviet Union did not recognize foreign copyrights at the time, and neither Baum nor his family received any royalties for it. Volkov's version was published under the title The Wizard of Emerald City (Волшебник Изумрудного Города) and the country where the story takes place was changed from Oz, to "Magic Land". Volkov also took many liberties with the text itself, editing as he saw fit, and adding a chapter in which Dorothy, now renamed Ellie, is kidnapped by a man-eating Ogre and rescued by her friends. The Wizard is renamed "James Goodwin", the Scarecrow is called "Strasheela" (derived from a Russian word meaning "to scare"), and the Tin Woodman is called "the Iron Woodman". The four witches each have new names as well: Villina (The Good Witch of the North), Gingema (The Wicked Witch of the East), Bastinda (The Wicked Witch of the West), and Stella (The Good Witch of the South). Volkov subsequently wrote his own independent series of sequels to the book, even more tenuously based on Baum's books, including: Urfin Jus and His Wooden Soldiers, Seven Underground Kings, The Firey God of the Marrans, The Yellow Fog, and The Secret of the Deserted Castle. Some characters in these sequels have clear origins in the original Oz books, such as Ellie's uncle Charlie Black, who is a combination of Baum's Cap'n Bill and Johnny Dooit, and Volkov's last book invokes the Forbidden Fountain. The latter three sequels feature, instead of Ellie and Toto, her younger sister Annie along with her own dog, Toto's grandson Arto, and her childhood friend Tim. Baum's original version and all of its sequels were later translated in a more faithful fashion, and Russians now see these two versions as wholly different series. In 1959, illustrations by Leonid Vladimirsky depicted Volkov's Scarecrow as short, round and tubby; his influence is evident in illustrations for translations across the Soviet bloc, where the Scarecrow is almost always portrayed in this manner. Vladimirsky has written at least two additional sequels to Alexander Volkov's alternative Oz; two more Russian authors and one German have written additional sequels to the "Magic Land" stories. The books have been faithfully translated to English by Peter Blystone as Tales of Magic Land. These last two books were previously made available as Oz books through Buckethead Enterprises of Oz, but were translated loosely to make them Oz books.

References to The Wizard of Oz (and Magic Land) are thoroughly ingrained in British, American, Russian, and many other cultures. A mere sampling of the breadth in which it is referenced includes Futurama, Family Guy and Scrubs (the former parodied it in an episode, the latter based an episode on it), The Cinnamon Bear (a 1938 radio serial), RahXephon (a 2002 Japanese animated television show), Zardoz (a 1974 Sean Connery movie), Avatar (a 2009 fantasy film)[13], The Dark Tower IV: Wizard and Glass (a 1997 Stephen King fantasy/Western novel), World of Warcraft(in the form of a boss fight), and the science fiction literature of Robert A. Heinlein, particularly The Number of the Beast. The Wizard of Oz Mystery, a murder mystery game based on the famous characters was released in 2007 from Shot In The Dark Mysteries. John Connor, a character in the Terminator series who sometimes uses the alias John Baum (presumably in honor of L. Frank Baum), stated that one of his favorite memories was of his mother reading him the story of the Wizard of Oz in Spanish as a child. The terminator series also references the Wicked Witch, Scarecrow and Tin [wood]man in a few episodes. The character of Cypher in the 1999 movie The Matrix explicitly quotes a part of a line from the original book. In the film, Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, reporter Polly Perkins meets with scientist Walter Jennings at Radio City Music Hall during a showing of the 1939 The Wizard of Oz film.

In 1967, The Seekers recorded "Emerald City", with lyrics about a visit there, set to the melody of Beethoven's "An die Freude".

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, by Gregory Maguire is a revisionist look at the land and characters of Oz. It was later made into a musical (also titled Wicked) that premiered on Broadway in 2003.

Many of these draw more directly on the 1939 MGM Technicolor film version of the novel, a now-classic of popular culture shown annually on American television from 1959 to 1991, and shown several times a year every year beginning in 1999.[14]

Critical response

The novel received good critical notices upon release; The New York Times wrote in September 1900:

[The Wonderful Wizard of Oz] is ingeniously woven out of commonplace material. It is of course an extravaganza, but will surely be found to appeal strongly to child readers as well as to the younger children … [the book] rises far above the average children's book of today, high as is the present standard.[15]

In modern times, it is widely held as a classic of children's literature; however, it has repeatedly come under fire over the years. Some religious commentators, for example, have objected to Baum's portrayal of "good witches".[10] On a more secular note, feminist author Margery Hourihan has described the book as a "banal and mechanistic story which is written in flat, impoverished prose" and dismissed the central character from the movie adaptation of the book as "the girl-woman of Hollywood".[16]

Adaptations

The Wizard of Oz has been adapted to other media numerous times, most famously in the 1939 film starring Judy Garland. There have been several preceding stage and screen adaptations, as well as subsequent stage and screen adaptations and sequels for theatrical release, television broadcast, and home video. The story has been translated into other languages (at least once without permission), and adapted into comics several times. Following the lapse of the original copyright, the characters have been adapted and reused in spin-offs, unofficial sequels, and reinterpretations, some of which have been controversial in their treatment of Baum's characters.

International rights

- In Canada, the Trademark "Wizard of Oz" is owned by EnTechneVision Inc. and has been licenced to the online children's network KIDOONS Inc.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ On May 17, 1900 the first copy of the book came off the press; Baum assembled it by hand and presented it to his sister, Mary Louise Baum Brewster. The public saw the book for the first time at a book fair at the Palmer House in Chicago, July 5–20. The book's copyright was registered on Aug. 1; full distribution followed in September. Katharine M. Rogers, L. Frank Baum, pp. 73–94.

- ↑ Oz Reference Home Page

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Baum, L. Frank; Hearn, Michael Patrick (1973). The Annotated Wizard of Oz. New York: C.N. Potter. pp. 38. ISBN 0-517-500868. OCLC 800451.

- ↑ The Writer's Muse: L. Frank Baum and the Hotel del Coronado

- ↑ Schwartz, Evan I. (2009). Finding Oz: how L. Frank Baum discovered the great American story (illustrated ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 273. ISBN 0547055102.

- ↑ Henry Littlefield, "The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism," American Quarterly 16 (Spring, 1964), p. 50. The full text of this article is also online at www.amphigory.com/oz.htm.

- ↑ Setting the Standards on the Road to Oz, Mitch Sanders, The Numismatist, July 1991, pp 1042-1050

- ↑ David B. Parker, "The Rise and Fall of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as a Parable on Populism," Journal of the Georgia Association of Historians, 15 (1994), pp. 49-63.

- ↑ Responses to Littlefield - The Wizard of Oz - Turn Me On, Dead Man

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gjovaag, Eric (2006). "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Frequently Asked Questions: The Books". The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Website. http://thewizardofoz.info/faq02.html#20. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ↑ Rutter, Richard. Speech Indiana Memorial Union, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana (July 2000).

- ↑ "Friends of the Emerald City (Volkov's)", EmeraldCity.ru

- ↑ "James Cameron on 'Avatar': Like 'Matrix,' 'This movie is a doorway'". Los Angeles Times. August 10, 2009. http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/herocomplex/2009/08/james-cameron-on-avatar-like-the-matrix-this-movie-is-a-doorway-.html. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/oz/ozsect2.html To See The Wizard:Oz on Stage and Film]. Library of Congress, 2003.

- ↑ "Books and Authors" (PDF). The New York Times: pp. BR12–13. 1900-09-08. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9D00E2D9153FE433A2575BC0A96F9C946197D6CF. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- ↑ Houihan, Margaret. Deconstructing the Hero. pp. 209. ISBN 0-415-14186-9. OCLC 36582073.

References

- Aycock, Colleen and Mark Scott (2008). Joe Gans: A Biography of the First African American World Boxing Champion. McFarland & Co, 133-139.

- Baum, Frank Joslyn; MacFall, Russell P. (1961). To Please a Child. Chicago: Reilly & Lee Co.

- Culver, Stuart. "Growing Up in Oz." American Literary History 4 (1992) 607–28.

- Culver, Stuart. "What Manikins Want: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors", Representations, 21 (1988) 97–116.

- Dighe, Ranjit S. (ed.) The Historian's Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum's Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory (2002)

- Gardner, Martin; Nye, Russel B. (1994). The Wizard of Oz and Who He Was. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press

- Gardner, Todd. "Responses to Littlefield" (2004), online

- Greene, David L.; Martin, Dick (1977). The Oz Scrapbook. Random House.

- Hanff, Peter E and Douglas G. Greene (1988). Bibliographia Oziana: A Concise Bibliographical Checklist. The International Wizard of Oz Club. ISBN 978-1-930764-03-3

- Hearn, Michael Patrick (ed). (2000, 1973) The Annotated Wizard of Oz. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-04992-2

- Littlefield, Henry. "The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism." American Quarterly. v. 16, 3, Spring 1964, 47–58.

- Parker, David B. (1994) "The Rise and Fall of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as a 'Parable on Populism'." Journal of the Georgia Association of Historians. 16 (1994): 49–63

- Riley, Michael O. (1997) Oz and Beyond: The Fantasy World of L. Frank Baum. University of Kansas Press ISBN 0-7006-0832-X

- Ritter, Gretchen. "Silver slippers and a golden cap: L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and historical memory in American politics." Journal of American Studies (August 1997) vol. 31, no. 2, 171–203.

- Rockoff, Hugh. "The 'Wizard of Oz' as a Monetary Allegory," Journal of Political Economy 98 (1990): 739–60 online at JSTOR

- Rogers, Katharine M. L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz. New York, St. Martin's Press (2002).

- Sherman, Fraser A. (2005). The Wizard of Oz catalog: L. Frank Baum's novel, its sequels and their adaptations for stage, television, movies, radio, music videos, comic books, commercials and more. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0786417927

- Sunshine, Linda. All Things Oz (2003)

- Swartz, Mark Evan. Oz Before the Rainbow: L. Frank Baum's "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" on Stage and Screen to 1939 (2000).

- Velde, Francois R. "Following the Yellow Brick Road: How the United States Adopted the Gold Standard" Economic Perspectives. Volume: 26. Issue: 2. 2002. also online here

- Ziaukas, Tim. "100 Years of Oz: Baum's 'Wizard of Oz' as Gilded Age Public Relations" in Public Relations Quarterly, Fall 1998

External links

| Wikisource has the complete text of:

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

|

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz at Project Gutenberg

- "Down the Yellow Brick Road of Overinterpretation," by John J. Miller in the Wall Street Journal

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Audio Book a Librivox project.

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900 illustrated copy), Publisher's green and red illustrated cloth over boards; illustrated endpapers. Plate detached. Public Domain – Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA.

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, full text and audio.

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, an unabridged dramatic audio performance at Wired for Books.

- The Baum Bugle: A Journal of Oz published by The International Wizard of Oz Club, provides frequent critical and historical information about L. Frank Baum and the Oz Series.

| The Oz books | ||

| Previous book: N/A |

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz 1900 |

Next book: The Marvelous Land of Oz |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||